GEORGES

CUVIER,

FOSSIL

BONES,

and

GEOLOGICAL

CATASTROPHES

______

New Translations & Interpretations

of the Primary Texts

______

MARTIN

J. S. RUDWICK

The University of Chicago Press  Chicago and London

Chicago and London

|

2

LIVING AND

FOSSIL ELEPHANTS

______

In 1795, three years after Cuvier told his friends in Germany about

Deluc's latest theory, the political situation in Paris became more

stable, or at least more favorable for

scientific work. During the Terror, the most radical and violent phase

of the Revolution, many of the old institutions of science had been abolished,

or at least disrupted. Many of the most influential savants had fled from

the capital.1 Some, most notably the great chemist (and tax

collector) Lavoisier, had even lost their lives at the guillotine. Now

yet another coup d'étar had given France a politically more moderate

government, the so-called Directory, which quickly showed itself more

favorable to the sciences than any since the start of the Revolution.

Cuvier therefore made a bold and risky decision to move to Paris in

search of a scientific career. In this he was encouraged by meeting

a scientific refugee from the capital, who wrote to colleagues there

on his behalf. Cuvier had already sent some articles (on invertebrate

zoology) to be published in Paris, but he was still scarcely known,

and had no certainty of gaining any position. In the event, however,

he could hardly

FIGURE 3 A portrait of Georges Cuvier at the age of

twenty-six--possibly a self-portrait--drawn in 1795, around the time

he moved to Paris; it may have been made to further his career prospects.

have arrived at a more propitious time. As a result of the Terror,

the old networks of patronage that had been essential for making a

career in science had been thrown into disarray, and had yet to be

reconstituted; a young man of talent had more opportunities than ever

before (fig. 3).

Given Cuvier's interests, it is not surprising that he focused his

attention on the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle (National

Museum of Natural History). Almost alone among the major scientific

institutions in Paris, this had escaped abolition, because at the height

of the Revolution it had reformed itself in a politically correct manner.

Although new in name, it was in fact the direct successor of the old

royal botanical garden (Jardin du Roi) and the associated royal museum

(Cabinet du Roi). Here at the new Muséum,2 Cuvier

managed--not without opposition--to obtain a junior position as understudy

(suppléant) to Mertrud, the elderly and undistinguished

professor of animal anatomy. The Muséum was to be Cuvier's professional

home, and, before long, his domestic home too, for the rest of his life.

Even a modest position at the Muséum placed Cuvier at the world

center for the natural history sciences, and its incomparable collections

became at once his most important resource. Before the end of the year,

his lecture course on comparative anatomy at the Muséum (standing

in for his nominal superior) showed Parisian savants that he was a newcomer

to be reckoned with. He put his science firmly on the map, by explaining

his conception of organisms--though it was not original to him--as functionally

integrated "animal machines."

A few weeks earlier, in one of its major acts of cultural politics,

the Directory had approved the foundation of a new Institut National.

This was intended to repair the revolutionary damage to French science

and scholarship, by bringing together in one prestigious body all the

branches of knowledge formerly cultivated in the various learned "academics"

that had been suppressed. Among these was the old Académic Royale

des Sciences (Royal Academy of Sciences), which was in effect revived

as the Institut's "class for mathematical and physical sciences."

Significantly, it was termed the First Class of the Institut

(in modern terms the three classes covered, roughly and respectively,

mathematics and the natural sciences, the social sciences, and the humanities).

Only a week after Cuvier's inaugural lecture, and doubtless partly

as a result of that event, he was elected the youngest member of the

First Class. Just as the Muséum became the site of his actual

research, so the Institut became the main arena for the exposition of

his scientific results, as several of the texts in this volume show.

Cuvier's rise to prominence in Parisian science in the years that followed

continued to be meteoric, but it was not effortless. Like any scientific

career in this period, it required the painstaking construction of networks

of patrons and allies, and discreet campaigns against rivals on all

sides.

Once installed in the Muséum, however precariously at first,

Cuvier picked up the research on comparative anatomy that he had started

in Normandy. He began to produce important papers on the anatomy of

the then poorly understood marine invertebrates, particularly the mollusks.

But the resources of the Muséum quickly turned his attention

to the vertebrates too, and above all to the mammals. More specifically,

he soon saw that some recent acquisitions to the Muséum's collections

might make it possible to settle a long-standing problem with far-reaching

implications.

It had long been known that large fossil bones and teeth were found

widely scattered in northern latitudes, in both the Old World and the

New, in "superficial" deposits close to the surface of the

ground. They were far from the tropical habitats of all the known large

mammals such as elephants and rhinoceros. The identification of these

fossil bones, and the explanation of their anomalous geographical position,

had long been matters of lively international debate among naturalists.3

Louis Jean Marie Daubenton (1716-99), now the professor of mineralogy

at the Muséum and one of Cuvier's senior colleagues, had been

a major contributor to this debate before the Revolution; and George

Louis Leclerc, count de Buffon (1707-88), for almost half a century

the director (intendant) of the Muséum's forerunner, had

made the fossil bones a key component in his overarching "theory

of the earth." So Cuvier was entering a well-trodden field.

He had one major empirical advantage over his predecessors. Among

the incidental spoils of the revolutionary wars were the outstanding

collections of the former ruler of the conquered Netherlands. What had

recently reached Paris included not only paintings and other items of

great artistic importance, but also a major natural history collection.

It included specimens that, added to those already at the Muséum,

proved to Cuvier's satisfaction that the living African elephant was

not the same species as the Indian, as had been commonly supposed; and

that the fossil elephant or "mammoth" was anatomically

distinct from either. Cuvier was not the first naturalist to suspect

this; but he alone had both the means and the skill to demonstrate it

persuasively.

Just a year after his arrival in Paris, he presented his first paper

to the Institut, setting out this argument. A summary of the paper (text

3) was published soon afterward in the Magasin encyclopédique

(Encyclopedic magazine), a newly founded journal for all the sciences,

which took its inspiration from the great French Encyclopédie,

the supreme emblem of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment. The full

version was published three years later in the Institut's new Mémoires, with several

plates of engraved illustrations based on his own drawings of the

crucial evidence (see fig. 4).4

Cuvier's first major paper displayed remarkable self-assurance--some

might term it arrogance--for a twenty-six-year-old with little scientific

achievement to his name. Emphasizing the importance of a critical

evaluation of factual claims, he confidently rejected the opinions

of his distinguished predecessors, on the grounds that their observations

had been insufficiently precise. He presented his conclusions about

the three distinct species of elephants as a triumph for his own

scrupulously exact methods of osteological comparison. Almost in

passing, he dismissed any suggestion that the differences might

be due to the transformation (in modern terms, evolution) of one

species into others--a notion that in general terms was being actively

canvassed in Paris at this time--and maintained that to abandon

the concept of the stability of natural species would be to subvert

the whole taxonomic enterprise. But he was careful to argue that

his anatomical approach could only enrich and deepen the traditional

zoological emphasis on the externally visible characters of animals.

This related his work tactfully to that of an even more youthful

colleague, the professor of zoology Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire

(1772-1844), who had helped him gain his position at the Muséum.

Cuvier also presented his work as a demonstration of the way comparative

anatomy could be an ancillary but essential tool for establishing

the "theory of the earth," or "geology," on

less speculative foundations. He argued that his research had undermined

the impressive edifice of the celebrated theory of the earth that

Buffon had expounded in his "Époques de la nature"

(Epochs of nature, 1778). This had been centered on the idea--not

original to Buffon--that the earth had had its origin as an incandescent

body in space, and that it had cooled gradually to its present surface

temperature. Buffon had assumed that the bones found in northern

lands were those of elephants and other tropical species, and had

therefore used them as evidence of a formerly warmer climate at

high latitudes. But if, as Cuvier now argued, the mammoth was not

the same species as either of the living elephants, it could well

have been adapted to a quite different environment, namely to the

cold climates in which its bones were now found; Buffon's argument

for a cooling earth, or at least his use of the bones as evidence

for it, would then collapse.

Cuvier's inference left new problems, however, above all that

of accounting for the difference--as he claimed it to be--between

all the

known fossil species and those now alive. In fact, when he first presented

his paper, he made his claim even more sweeping than it appeared in

print, because he extended this absolute contrast between fossil and

living species to marine animals as well as such terrestrial

species as the elephants. But after his lecture the "learned conchologists"

he had cited must have rejected that claim, insisting that some marine

mollusks did have exact "analogues" among fossil shells.5

Even with an implicit restriction to terrestrial animals, however, his

published claim was striking enough.

Cuvier claimed--though without detailed argument--that the evidence

pointed to an earlier and prehuman "world" that had

been "destroyed by some kind of catastrophe." This was a theme

that, though not original to him, was to pervade his geological theorizing

for the rest of his life. Although he did not explain why the event

must have been sudden, he did imply that it was not unique, and that

it might be repeated in the future. But he deftly drew back from further

speculation of this kind, leaving such matters to a bolder--or perhaps

more foolhardy--"genius." This was a neat way of deferring,

though with more than a touch of irony, to his senior colleague Barthélemy

Faujas de Saint-Fond (1741-1819), who had boldly adopted Deluc's neologism

"geology" as the title of his professorship when the Muséum

was reconstituted.

TEXT

3

____

Memoir

on the Species of Elephants, Both Living and Fossil

Read at the public session of the National

Institute on

15 Germinal, Year IV [4 April 1796]6 by G. Cuvier7

CONSIDERABLE DIFFERENCES have long been noted between the elephants

of Asia and those of Africa, with regard to their size, their habits, and the places where they live; and Asiatic peoples have known since

time immemorial how to tame the elephants they use for hunting, whereas

African elephants have never been subdued, and are hunted only to eat

their flesh, to collect their ivory, or to eliminate the danger of their

presence. Nonetheless the authors who have dealt with the natural history

of elephants have always regarded them as forming one and the same species.

The first suspicions that there are more than one species came from

a comparison of several molar teeth that were known to belong to elephants,

and which showed considerable differences; some having their crown sculpted

in a lozenge form, the others in the form of festooned ribbons.

The arrival in Paris of the natural history collection acquired for

the Republic by the Treaty of The Hague has enabled us to turn these

suspicions into certainty.8 It contains two elephant skulls:

one, which has the teeth with festooned ribbons, comes from Ceylon;

the other, which has only diamond forms, is from the Cape of Good Hope.

A glance at these skulls is sufficient to observe, in their profile

and all their proportions, differences that do not allow them to be

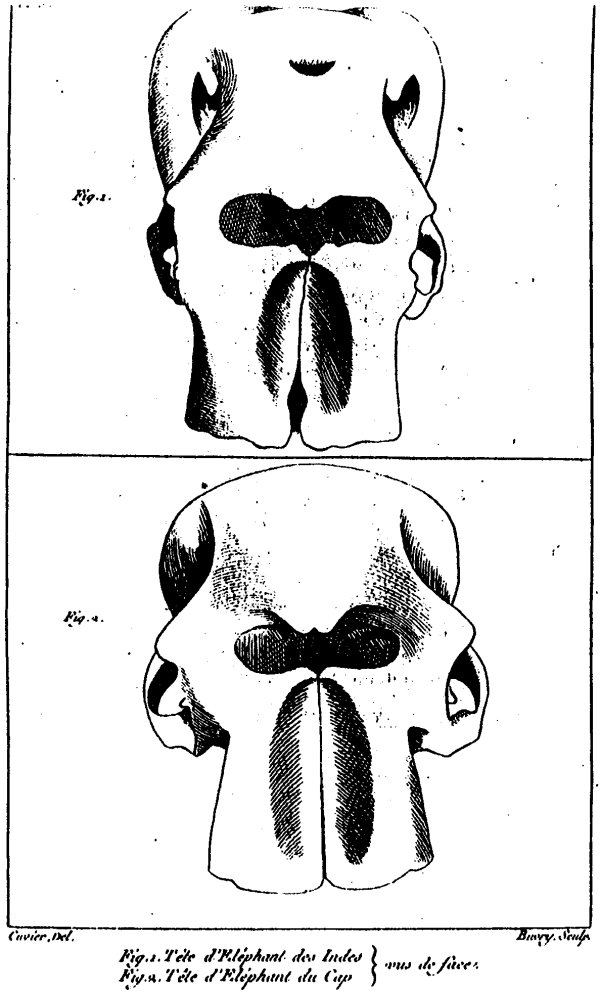

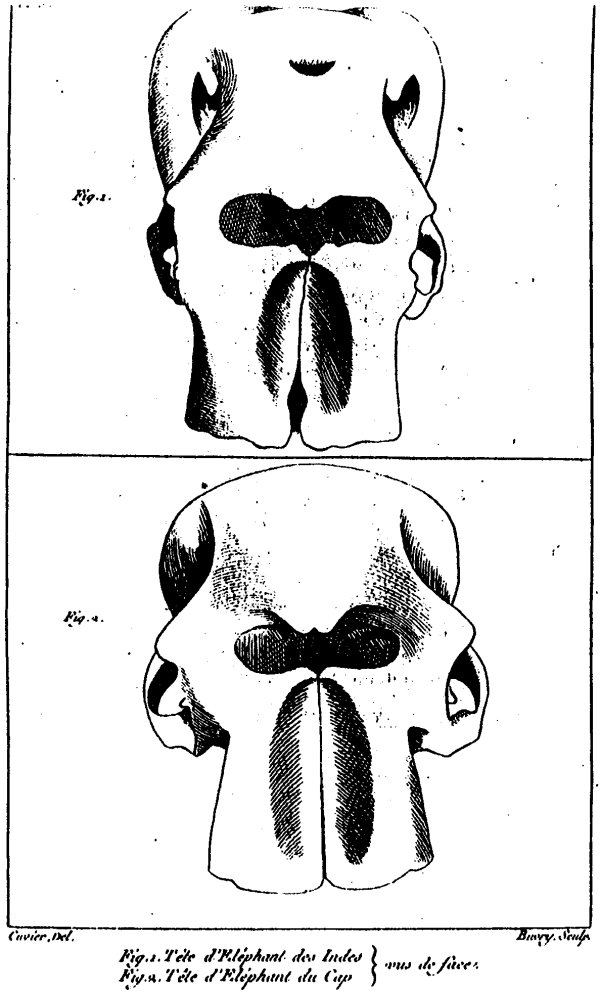

regarded as the same species (fig. 4). It is clear that the elephant

from Ceylon differs more from that of Africa than the horse from the

ass or the goat from the sheep.9 Thus we should no longer

be astonished if they do not have the same nature or the same habits.

It is to anatomy alone that zoology owes this interesting discovery,

which a consideration of the exterior of these animals would only have

been able

FIGURE 4 The skulls of elephants (top) from Ceylon

(now Sri Lanka), south of the Indian mainland, and (bottom)

from the Cape of Good Hope (now in South Africa), engraved from Cuvier's

drawings and published in 1799 with the full text of his paper.

to render imperfectly.10 But there is [also]

a science that does not appear at first sight to have such close affinities

with anatomy; one that is concerned with the structure of the earth,

that collects the monuments of the physical history of the globe,

and tries with a bold hand to sketch a picture of the revolutions

it has undergone:11 in a word, it is only with

the help of anatomy that geolog).12 can establish

in a sure manner several of the facts that serve as its foundations.

Everyone knows that bones of enormous animals are found underground

in Siberia, Germany, France, Canada,13 and even Peru, and

that they cannot have belonged to any of the species that live today

in those climates. The bones that are found, for example, throughout

the north of Europe, Asia, and America resemble those of elephants so

closely in form, and in the texture of the ivory of which their tusks

are made, that all savants hitherto have taken them to be the same.

Other bones have appeared to be those of rhinoceros, and they are indeed

very similar: yet today there are elephants and rhinoceros only in the

tropical zone of the Old World. How is it that their carcasses are found

in such great numbers in the north of both continents?

On this point, one is left with [mere] conjectures. Some [writers]

have invoked great inundations that have transported them there; others

suppose that southern peoples led them there in some great military

expeditions.14 The inhabitants of Siberia believe quite simply

that these bones come from a subterranean animal like our moles, which

never lets itself be taken alive; they name it "mammoth,"

and mammoth tusks, which are similar to ivory, are for them a quite

important item of commerce.

None of this could satisfy an enlightened mind [un esprit éclairé].

Buffon's hypothesis15 was more plausible, if we assume that

it was not contentious for reasons of another kind. According to him,

the earth had emerged burning from the mass of the sun, and had started

to cool from the poles; it was there that living nature had begun. The

species that formed first, Which had more need of warmth, had been chased

successively toward the equator by the increasing cold; and since they

had traversed all the latitudes, it was not surprising that their remains

were found everywhere.

A scrupulous examination of these bones, made by anatomy, will relieve

us of having recourse to any of these explanations, by teaching us that

they are not similar enough to those of the elephant to be regarded

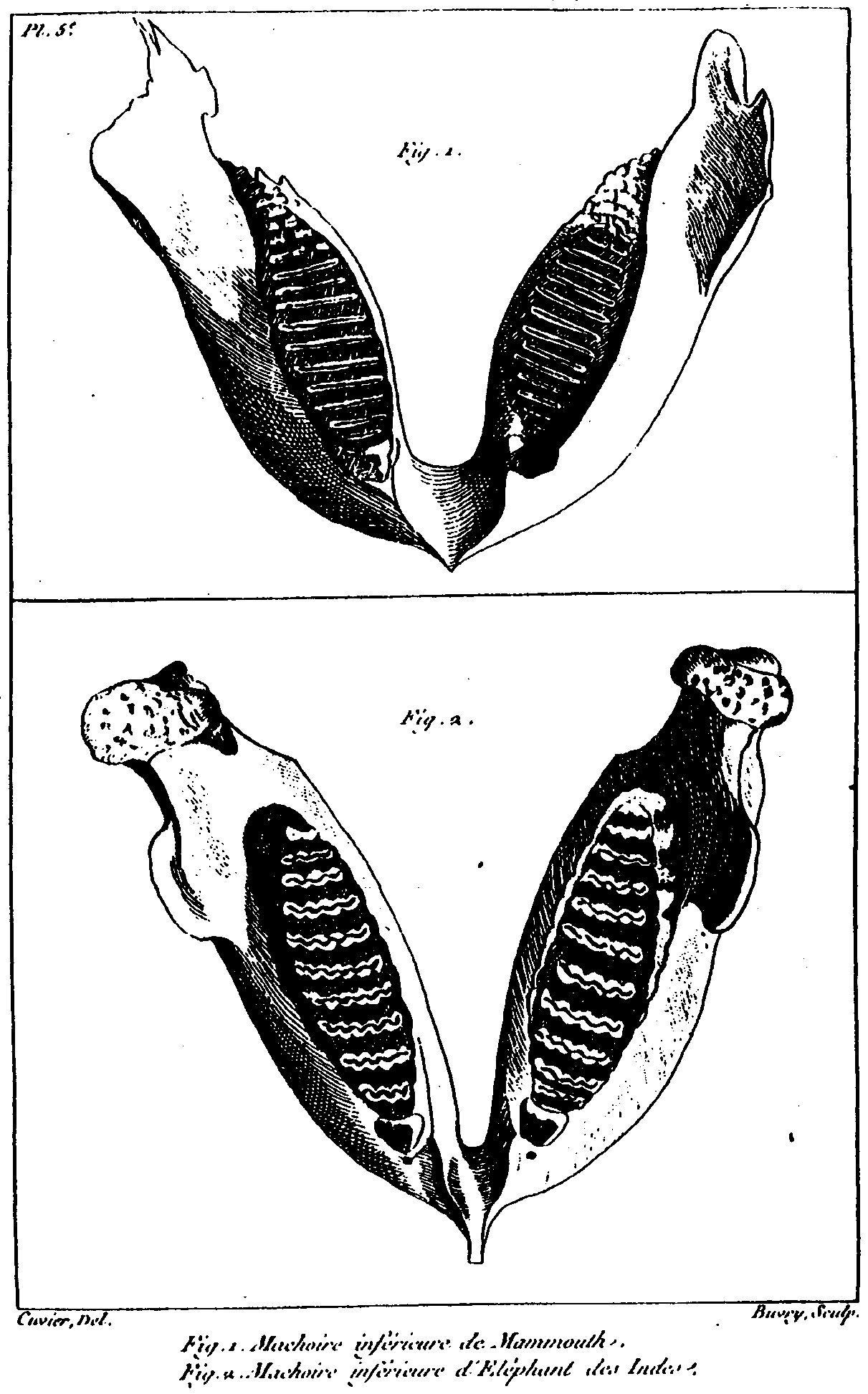

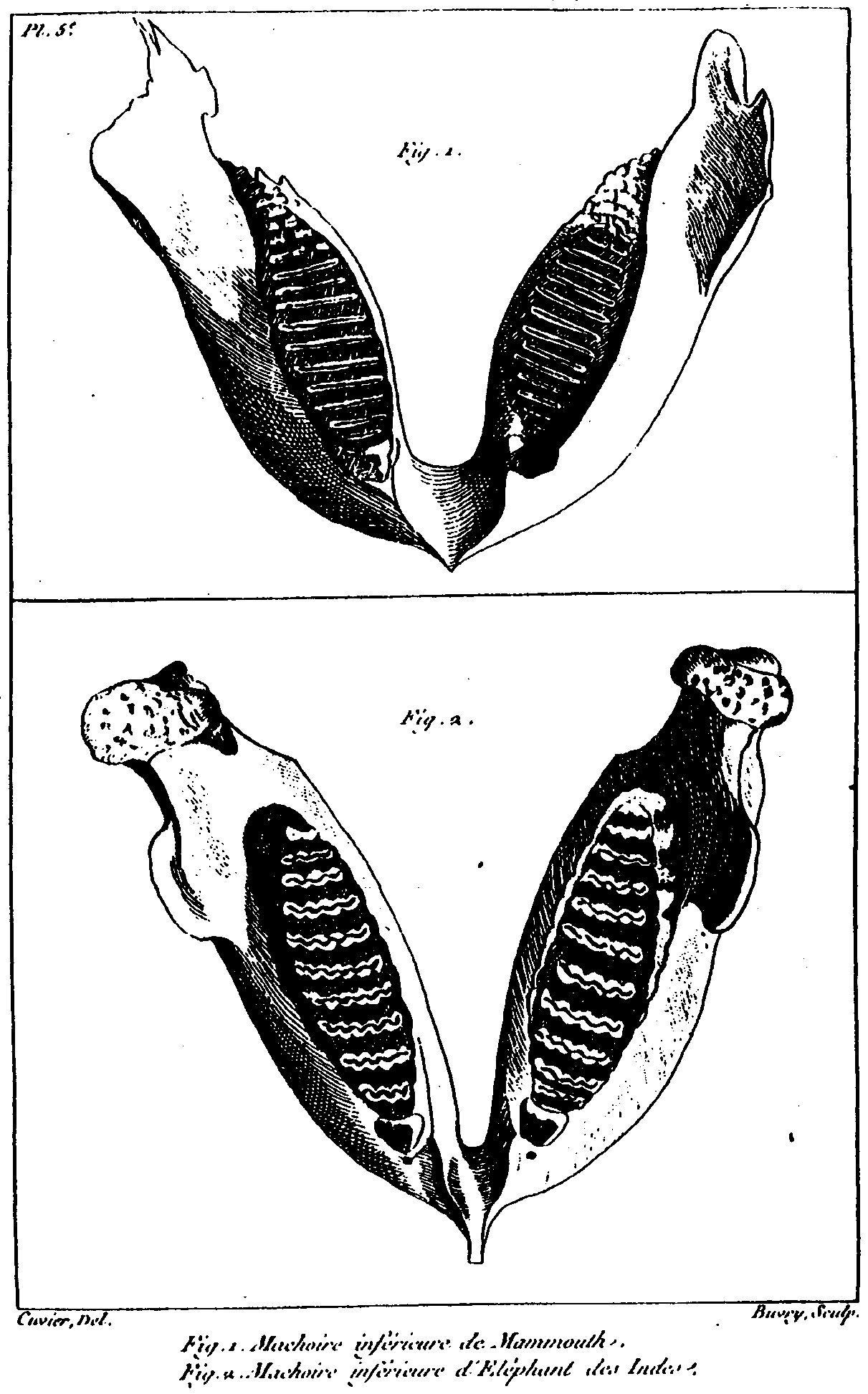

as absolutely from the same species. The teeth and jaws of the mammoth

do not exactly resemble those of the elephant [fig. 5]; while as for

the same parts of the Ohio animal, a glance is sufficient to see that

they differ still further.16

These [fossil] animals thus differ from the elephant as much as, or

more than, the dog differs from the jackal and the hyena. Since the

dog tolerates the cold of the north, while the other two only live in

the south, it could be the same with these animals, of which only the

fossil remains are known.

However, while relieving us of the necessity of admitting a gradual

cooling of the earth, and while dispelling the gloomy ideas that presented

the imagination with northern ice and frost encroaching on countries

that today are so pleasant, into what new difficulties do these discoveries

not now throw us?

What has become of these two enormous animals of which one no longer

finds any [living] traces, and so many others of which the remains are

found everywhere on earth and of which perhaps none still exist? The

fossil rhinoceros of Siberia are very different from all known rhinoceros.

It is the same with the alleged fossil bears of Ansbach;17

the fossil crocodile of

FIGURE 5 The lower jaw of the mammoth (top) compared with that

of the Indian elephant (bottom), engraved from Cuvier's drawings

and published in 1799 with the full text of his paper.

Maastricht; the species of deer from the same locality;18

the twelve-foot-long animal, with no incisor teeth and with clawed digits,

of which the skeleton has just been found in Paraguay [see fig. 6]:

none has any living analogue.19 Why, lastly, does one find

no petrified human bone?

All these facts, consistent among themselves, and not opposed by any

report, seem to me to prove the existence of a world previous to ours,

destroyed by some kind of catastrophe.20 But what was this

primitive earth? What was this nature that was not subject to man's

dominion? And what revolution was able to wipe it out, to the point

of leaving no trace of it except some half-decomposed bones?

It is not for us [i.e. Cuvier himself] to involve ourselves in the

vast field of conjectures that these questions open up. Only more daring

philosophers undertake that. Modest anatomy, restricted to detailed

study and to the scrupulous comparison of the objects submitted to its

eyes and its scalpel, will be content with the honor of having opened

up this new highway to the genius who will dare to follow it.

Translated from Cuvier, "Espéces des éléphans"

(Species of elephants, 1796).

____________________

1. The contempotary term "savants"

(which was used in English as well as in French) will be used throughout

this volume, in place of the misleadingly anachronistic term "scientists."

Savants could be learned, expert, or "savant" in any of a

wide range of subjects, not just those covered by the modern anglophone

meaning of "science"; and they might or might not be "professionals"

in the sense of earning their living from such studies.

2. The accent and initial capital will serve

hereafter to indicate reference to this specific museum--at the time,

the greatest natural history museum in the world.

3. "Naturalists" was the contemporary

term for those who studied the sciences of "natural history"

such as zoology, botany, and mineralogy; neither term had its modern

pejorative overtones of amateurism. "Naturalists" were, in

effect, a subset of the larger category of "savants."

4. Cuvier had shown outstanding talent as a

biological artist even in his youth; he continued throughout his life

to make most of his own drawings, though they then had to pass through

the hands of professional engravers before publication.

5. The relevant passage in the manuscript (MS

628, Bibliothéque Centrale, Muséum National d'Histoire

Naturelle, Paris) was omitted from the first published text of the paper

(translated below as text 3) and its subsequently enlarged versions:

see Burkhardt, Spirit of system (1977), P. 129 and n. 56.

6. [The date, like several others in this volume,

is given in the form of the Republican calendar. This was introduced

at the height of the Revolution as part of the effort to eliminate all

traces of the culturally Christian past. It had its nominal origin at

the declaration of the French Republic in September 1792 (though it

was not introduced until Year II, or 1793-94); it divided the year (beginning

in September) into twelve new months based on the seasonal weather.

The Republican calendar was dropped, and the ordinary (Grègorian)

calendar resumed, at the start of 1806. (In this volume Republican years

will be denoted by Roman numerals, as they often were at the time.)]

7. This article is an abstract of a detailed

paper that will be printed in the Institute's collection,

accompanied by the necessary descriptions and illustrations [Cuvier, "Espéces

d'éléphans" (Species of elephants, 1799)].

8. [The treaty established the terms of peace

between the victorious French and the Dutch they had defeated. As Part

of the officially sanctioned cultural looting of the Netherlands, the

fine natural history collection of the Stathouder, the Dutch ruler who

had fled to England, was removed to the Muséum in Paris.]

9. [The full text of the paper has at this point

one of Cuvier's most trenchant statements of his rooted opposition to

evolutionary interpretations of organic diversity: "I believe that,

after reading this comparative description, which I have made with all

possible care and precision, and for which the original specimens exist

in the comparative anatomy collection at the Muséum, no naturalist

can doubt that there are two quire distinct species of [living] elephants.

Whatever may be the influence of climate to make animals vary, it surely

does not extend this far. To say that it can change all the proportions

of the bony framework [charpente osseuse], and the intimate texture

of the teeth, would be to claim that all quadrupeds could have been

derived from a single species; that the differences they show are only

successive degenerations; in a word, it would be to reduce the whole

of natural history to nothing, for its object would consist only of

variable forms and fleeting types [types fugaces]" (1799,

p.12). The word "dégénérations" was widely

used to denote changes within a species, forming some new variety;

but also, by at least some authors, for changes transforming one species

into another.]

10. [Cuvier and other naturalists of his generation

were critical of the zoology practiced by their predecessors (e.g. Buffon)

for having focused attention on the externally visible characters of

animals rather than the internal anatomy revealed by dissection. Cuvier

himself was highly skilled in practical dissection; in this respect

his studies of molluscan anatomy are even more striking than his work

on vertebrates, since they involved much finer manual dexterity.]

11. [In Cuvier's writing and that of his contemporaries,

the word "revolution" simply meant major changes in the course

of time: it was used for example in the writing of human history to

denote the slow rise and fall of civilizations; and in astronomy to

denote the regular orbiting of the planets round the sun. It had no

necessary connotations of suddenness, still less of violence.

In effect, what Cuvier termed "catastrophes" (see below) were

a special subset of "revolutions."]

12. [The emphasis is not indicated typographically

in the original, but is implied by the construction of the sentence.

It is important to remember that at this time the term was still a neologism

that had been adopted by very few writers other than its author Deluc

and Cuvier's colleague Faujas.]

13. ["Canada" included much of what

eventually became the United States: in particular, the uncolonized

country around the Ohio River, which yielded some of the most problematic

fossil bones.]

14. [A huge mass of water sweeping suddenly

across the continents (like the tsunamis associated with some submarine

earthquakes, but far larger) was a widely favored explanation for the

bones found in Siberia. The classical accounts of Hannibal's campaign

from North Africa, complete with some military elephants, had been the

basis for an earlier explanation of the fossil bones found in Europe,

but its plausibility had collapsed as more and more bones were found.]

15. [Buffon, "Époques de la nature"

(1778). As a leading philosopher of the Enlightenment, Buffon was an

"enlightened mind" par excellence.]

16. ["Ohio animal" referred to bones

first found in 1739 on the banks of the Ohio River (in what is now Kentucky):

their identity was much disputed during the rest of the eighteenth century,

and was not resolved until Cuvier later defined and named the animal

Mastodon.]

17. [The bones found in caves in a part of Bavaria

that at this time was in the territory of Ansbach, most famously in

caves around Muggendorf, between Erlangen and Bayreuth.]

18. [The "crocodile" was a spectacularly

large fossil found in underground quarries near the southern Dutch town.

The finest known specimen had recently been brought to Paris, like the

elephant skulls, as a trophy of war. It was described and illustrated

in a lavishly produced monograph by Faujas, Montague de Saint-Pierre

de Maestricht (Saint Peter's Mount at Maastricht, 1799). which he

must have been preparing at this time. It was later interpreted as a

huge marine lizard. and Cuvier named it Mosasaurus (lizard of

the Maas or Meuse) (see chapter 13). "Deer" referred to supposed

fossil antlers from the same Chalk formation at Maastricht, which Cuvier--once

he had seen the specimens--identified as parts of the carapace of a

marine turtle.]

19. ["Analogue" was the term used

in the contemporary debate about the reality or otherwise of extinction,

to denote a living species that was identical to one found fossil.

For the Paraguay animal, see text 4.]

20. [The full text of the paper has a significant

addition at this point: "beings whose place has been filled by

those: that exist today, which will perhaps one day find themselves

likewise destroyed and replaced by others" (1799, p. 21). For Cuvier

the present "world" bad no finality, and the "catastrophe"

that had made the mammoth extinct was certainly not a unique event,

and perhaps not even the last of its kind.]

|