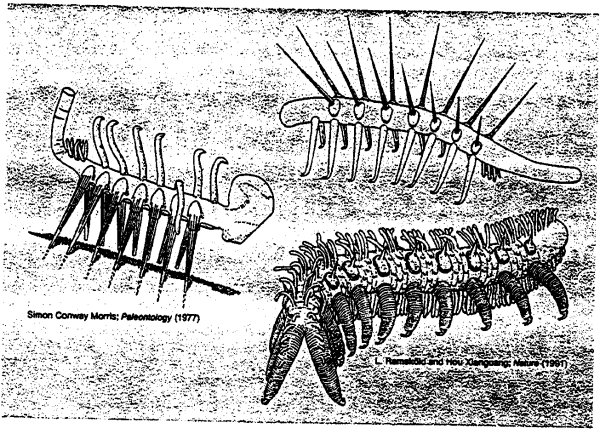

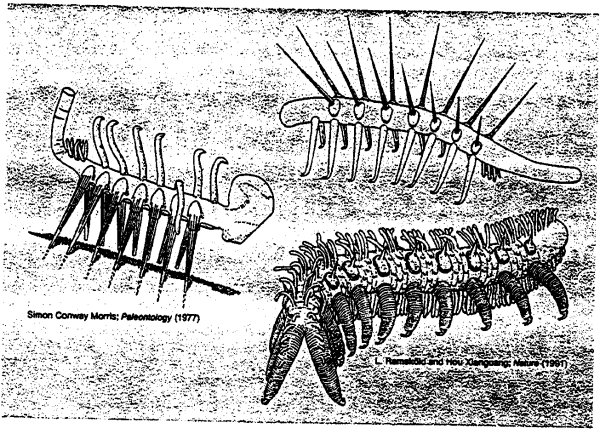

Left: Conway Morris's Original reconstruction of Hallucigenia, Right,

top and bottom; Ramskold and Hou's inversion of Hallucigenia as an onychophoran

and their reconstruction of the new Chengjiang onychophoran with side

plates and spines.

clearly bears interesting implications. This third way has been supported,

often by well-respected taxonomists, but our general preference for shoehorns

and straightening rods has given it short shrift. The Onychophora, under

this view, might represent a separate group, endowed with sufficient anatomical

uniqueness to constitute its own major division of the animal kingdom,

despite the low diversity of living representatives. After all, the criterion

for separate status should be degree of genealogical distinctness, not

current success as measured by number of species. A lineage may need a

certain minimal membership just to have enough raw material available

so that evolution can craft sufficient difference for high taxonomic rank.

But current diversity is no measure of available raw material through

geological history. Evolution is ebb and flow, waxing and waning; once

great groups can be reduced to a fraction of their past glory. A great

man once told us that the last shall be first, but just by the geometry

of evolution, and not by moral law, the first can also become last. Perhaps

the Onychophora were once a much more diverse group, standing wide and

tall in their distinctness, while Peripatus and its allies now

form a pitifully reduced remnant.

(By speaking of potential distinctness, I am not making any untenable--indeed

it would be nonsensical--claim for total separation without any relationship

to other phyla. Very few taxonomists doubt that onychophorans, along with

other potentially distinct groups known as tardigrades and pentastomes,

have their evolutionary linkages close to annelids and arthropods. But

this third view places onychophorans as a separate limb of life's tree--branching

off near the limbs of annelids and arthropods and eventually joining them

to form a major trunk--whereas the shoehorn would stuff onychophorans

into the Arthropoda, and the straightening rod would change life's geometry

from a tree to a line and place onychophorans between primitive worms

and more advanced insects.)

We can only test this third possibility by searching for onychophorans

in the fossil record--a daunting task because they have no preservable

hard parts and therefore do not usually fossilize. I write this essay

because several striking new discoveries and interpretations, all made

in the past year or two, now point to a markedly greater diversity for

onychophorans right at the beginning of modern multicellular life, following

the Cambrian explosion some 550 million years ago. These discoveries arise

from two fortunate and quite different circumstances: first, onychophorans

have been found in the rare soft-bodied faunas occasionally preserved

by happy geological accidents in the fossil record; second, some ancient

onychophorans possessed hard parts and can therefore appear in ordinary

fossil deposits.

I fully realize that this expansion in onychophoran diversity at the

beginning of multicellular animal life can scarcely rank as the hottest

news item of the year. Most readers of this column, after all, have probably

never heard the word onychophoran and, lamentably, have no acquaintance

with poor, lovely Peripatus. So why get excited about old onychophorans

if you never knew that modern ones existed in the first place? Do hear

me out

|