THIS

VIEW OF LIFE

Eight (or Fewer)

Little Piggies

Why do we and most other tetrapods have five digits on each climb?

by Stephen Jay Gould

Richard

Owen, England's greatest vertebrate anatomist during Darwin's generation,

developed the concept of an archetype to explicate the evident similarities

that join us with frogs, flamingoes, and fishes. (An archetype is an abstract

model constructed to generate the entire range of vertebrate design by

simple transformation of the all-inclusive prototype.) Owen was so pleased

with his conception that he even drew a picture of his archetype, engraved

it upon a seal for his personal emblem, and in 1852, wrote a letter to

his sister Maria, trying to explain this arcane concept in layperson's

terms:

It

represents the archetype, or primal pattern--what Plato would have

called the "divine idea" on which the osseous frame of all vertebrate

animals--i.e., all animals that have bones--has been constructed.

The motto is "the one in the manifold," expressive of the unity

of plan which may be traced through all the modifications of the pattern,

by which it is adapted to the very habits and modes of life of fishes,

reptiles, birds, beasts, and human kind.

Darwin

took a much more worldly view of the concept, substituting a flesh and

blood ancestor for a Platonic abstraction from the realm of ideas. Vertebrates

had a unified architecture, Darwin argued, because they all evolved from

a common ancestor. The similar shapes and positions ancestor. The similar

shapes and positions of bones record the historical happenstance of ancestral

form, retained by inheritance in all later species of the lineage, not

the abstract perfection of an ideal shape in God's realm of ideas. Darwin

burst Owen's bubble with a marginal note in his personal copy of Owen's

major work, On the Nature of Limbs. Darwin wrote: "I look

at Owen's archetype as more than idea, as a real representation as far

as the most consummate skill and loftiest generalization can represent

the parent form of the Vertebrata."

However

we construe the concept of an organizing principle of design for major

branches of the evolutionary tree--and Darwin's version gets the modern

nod over Owen's--the idea remains central to biology. Consider the

subset of terrestrial vertebrates, a group technically called Tetrapoda,

or four legged (and including amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals

in conventional classifications). Some fly, some swim, and others slither.

In external appearance and functional role, a whale and a hummingbird

seem sufficiently disparate to warrant ultimate separation. Yet we unite

them by skeletal characters common to all tetrapods, features that set

our modern concept of an archetype. Above all, the archetypal tetrapod

has four limbs, each with five digits--the so-called pentadactyl (five-fingered)

limb.

The

archetypal concept does not require that each actual vertebrate display

all canonical features, but only that uniqueness be recognized as extreme

transformation of the primal form. Thus, a whale may retain but the tiniest

vestige of a femur, only a few millimeters in length and entirely invisible

on its streamlined exterior, to remind us of the ancestral hind limbs.

And although a hummingbird grows only three toes on its feet, a study

of embryological development marks them as digits two, three, and four

of the full ancestral complement. The canonical elements are starting

points and generating patterns, not universal presences.

In the tetrapod archetype, no feature has been more generally accepted

than the pentadactyl limb, putative source of so many deep and transient

human activities, from piano playing to touch typing, duck shooting, celebratory

"high fives," and decimal counting (twice through the sequence

of "this little piggy ... ". Yet this essay will challenge the

usual view of such a canonical number, while not denying its sway in our

lives.

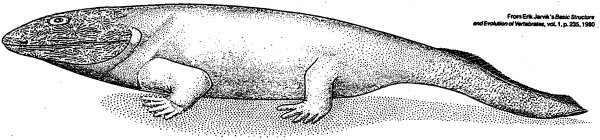

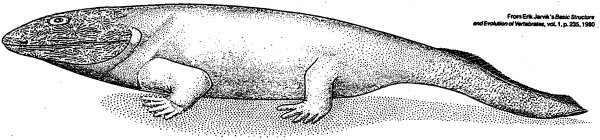

A reconstruction of Ichthyostega shows the early tetrapod with five

digits on each limb.

22 NATURAL HISTORY 1/91

|